Reflecting her first personal encounter with Samir Amin, the author believes that Samir Amin’s work will continue to be a tool for change and to challenge capitalism, especially in these days of rapidly rising inequalities.

On receiving the news of Samir Amin’s death, one of the first thoughts that struck me was that two of my greatest mentors have passed this way: tumours discovered quite suddenly. In the case of Giovanni Arrighi, nine years ago, when the tumours were discovered some ten months before his death, Giovanni recalled his grandfather who had always said of his grandson that he never did things in moderation. Giovanni’s tumours were several and therefore incurable, though he lived three times longer than the doctors had estimated upon detecting the cancer. In the case of Samir Amin it was cancer of the lungs, no doubt related to his years of chain smoking, as my close Kenyan sister (also a socialist and evolving chain smoker) pointed out to me when I began writing this piece. What all this makes me wonder about is the poisonous impact of speaking one’s mind and toiling to produce research to make critical arguments no matter how narrow the space within intellectual and political discourse.

But this is not the way I want to begin my tribute to Papa Samir Amin.

I want to start like the Namibians: thunderous applause—instead of a moment of silence — to celebrate the life of a loved one moving on to the ancestral world.

I want to start with Bakule! Bakule!,part of a West African praise song I first heard in 1998 at one of the many memorials held around the world for Kwame Ture —not unlike the memorials now being held for Samir Amin.

I want to start by evoking how Miriam Makeba came into my life. A copy of a pirate cassette made at Mama Miriam’s concert in Guinée Conakry in 1981. My father had purchased it in Nairobi that year, while trying to bring my ill grandfather (also a chain smoker) to Canada to pass in the home of his son, as was his last wish. The same live concert to which I would dance in London (now a CD) with my Sierra Leonean brother Victor, in the mid 1990s. And the same CD I would find again in Johannesburg 2015, in the music collection of my South African partner, Phumzile.

From his early works on the economic histories of Mali, Guinée, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal; to his work on the Maghreb; to his work on Congo; to his many works on imperialism and anti-imperialist unity — Samir Amin was a Pan-African internationalist of a journey to which I have always related as the Canadian-born child of East Africans who lived through colonialism and saw the early moments of independence.

One of the earliest works I read of Samir Amin was Empire of Chaos, in 1991, which for me, was among other things, a critique of the ahistorical notion of “globalisation” that was becoming hip around that time. Like Le Duan (Vietnam Workers’ Party), Mao Tse-Tung, William Pomeroy, Volodia Teitelboim (Communist Party, Chile), Amilcar Cabral, Samora Machel and Frantz Fanon — all of whom I read in my first and last political science course, in 1988 — Samir Amin’s questions and vision reflected the South-North world view and historical underpinnings with which I had been raised. They also took me beyond, to critical socialist imaginaries.

Some years later, while studying economic history, I came across samples of the more academic work of Samir Amin, including Neo-Colonialism in West Africa [[i]], upon which he likely began reflecting during his time as Advisor to the Ministry of Planning in Bamako. These careful studies of how local class interests interact with external class/national interests through formal colonial and postcolonial periods offer useful analytical tools and demonstrate how to apply them to generate non-Eurocentric historical materialist understanding. These are important for anyone wanting to understand how we have arrived at where we are today in Africa —whether the instances of outright dictatorship, the lack of multi-party democracy, or so-called democratic centralism.

In 2010, Firoze Manji — founder of Pambazuka Newsand another fiercely radical, independent thinker of the African continent — made a call for papers from young African intellectuals in honour of Samir Amin’s 80th birthday. The papers were to expound on “accumulation by dispossession” in African contexts – a notion of Marxist geographer, David Harvey, describing dynamics of neoliberal capitalism and arguably building on what Samir Amin has traced historically for the just over 500 year life of world capitalism. Using my updated conceptualisation of Amin’s “unequal exchange” as well as Harvey’s “accumulation by dispossession”, the paper I submitted was on the political economy of South-North nurse migration and the implications for societies in Africa. The three best papers were to be presented and publicised in three African cities to draw attention to the ideas of critical young intellectuals engaging the world in the footsteps of Papa Samir. A highlight of the programme was that authors of the papers would meet Samir Amin in person.

But finally it was only in 2011, after three decades of reading Samir Amin’s academic writing, popular books, and articles published in Monthly Review, that I finally encountered my mentor personally. On completing my research monograph, Rethinking Unequal Exchange - The Global Integration of Nursing Labour Markets, a friend of Ethiopian origin suggested I approach Samir Amin to write a foreword for the book. I initially wrote to Amin at an address I found online, gingerly evoking the world historical approach of my work and my background of studies with some of Samir’s good friends, Anibal Quijano, Immanuel Wallerstein and Giovanni Arrighi. Not receiving a response, I wrote a second time, this time in French, having obtained Papa Samir’s actual e-address through two contacts on either end of the world — Firoze Manji in Kenya and Claude Misukiewicz in New York City — reflecting Samir Amin’s reach. My friend had assured that he was open to such requests and in line with this, Papa Samir’s email response was brief, sweet and somewhat old school: “Friend, I will do it; send the manuscript in hard copy to my address in Paris.”

Reading Samir Amin’s foreword to my book was akin to being re-educated in one’s own speciality area. In it he provides the longue duréeof global migration, tracing the Americas and later, Australia, New Zealand and parts of South Africa, as the outlet for displaced European peasants, which was key to the relative smoothness of urbanisation and industrialisation in early Modern Europe. Contrasting this with contemporary cities of Africa, Asia and Latin America teeming with unemployed people who can no longer live off the land and do not have a similar outlet, Amin points to landlessness as one of the first impoverishments of historical capitalism, the democratic challenge of which Western European societies were spared.

Also in the foreword, Amin brilliantly quotes Evo Morales to make a point about the hypocrisy of temporary labour migration policies of rich countries today — something it took me close to an entire chapter of the book to explain. As Morales puts it, “European immigrants who appropriated lands and embattled indigenous peoples in the Americas did not carry visas.” This exemplifies Amin’s agility in the world of ideas: immersing himself in politics, activism, as well as research and analysis, unlike many leftist thinkers of our times who keep themselves aloof in the theories and canons of the proverbial ivory towers.

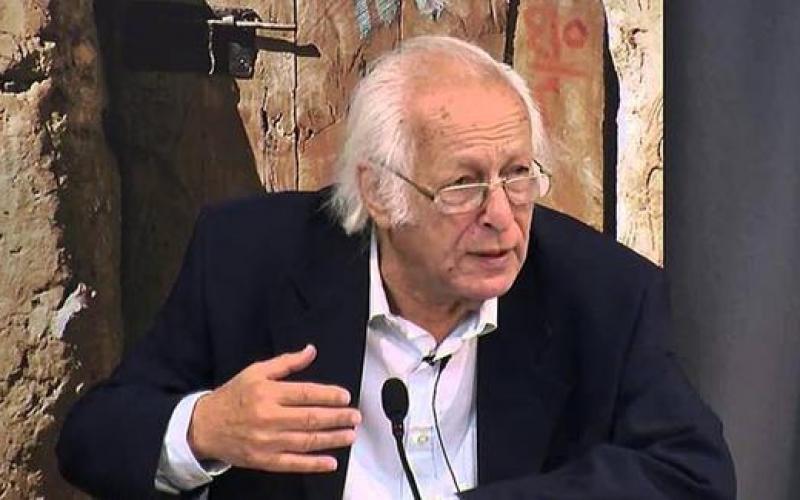

When we finally met in person in 2012, at a closed workshop in Nottingham on the subject of the historic inability to forge solidarity among workers’ unions of the global North and global South, I was taken aback by the concurrent larger-than-life magnitude and down-to-earth essence of this great Mwalimu, Samir Amin. Virtually the first thing we did together after greeting each other on the first night was smoke some cigarettes. When I saw him pull out a box of matches from a pocket after dinner I ventured to ask, hoping to crack a smile, “Est-ce que c’est pour fumer des cigarettes?” With a hearty laugh, Papa Samir exclaimed “Oui!”and we left the room immediately.

The next morning at the workshop we sat side by side. When I brought out some bags of dates and almonds, which I had carried from home in anticipation of the tryingness of English food, I gestured to Papa Samir that he help himself. By noon the bags were near empty, Papa Samir having partaken with the familiarity of a long lost friend, which perhaps is precisely what he was.

*

Samir Amin is arguably most known for his work in political economy — among others, his notions of the globalised law of accumulation, unequal development, monopoly capitalism (together with Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy), and delinking. But as a historian pointed out at a recent event in Toronto celebrating Samir Amin’s life, work and politics, Amin made original contributions to several subjects, including the history of civilisations. His formulation of the tributary mode of production is a corrective of West-centred, historical materialism, which entails only three modes: the slave mode, the feudal mode and the capitalist mode. In “Revolution or Decadence?”,what would be one of his last pieces in Monthly Review(May 2018), Amin refreshes our memory on the tributary mode. Amin argues that unlike the slave mode — which follows only from extended commodity relations — the tributary and capitalist modes are universal.

The establishment and subsequent disintegration of the Roman Empire signified a premature attempt at tributary construction in a context where the level of development of the productive forces did not require tributary centralisation. Only following the feudal fragmentation that led to absolutist monarchies did the West approach the complete tributary model of which imperial China is the highest expression. This explanation of the uniqueness of the West — rooted in its relative underdevelopment — is one that counters the Western exceptionalism typically referenced around the world to this day. More broadly, Amin’s formulation of the tributary mode reflects his methodological ability to embrace historical contingency while maintaining a handle on the dynamics of a systemic whole — features of thinking quite foreign to what Amin called “Marxology”, the tone deaf repetition of what Marx wrote of his own times as explanations of the present.

But eye on the prize, Amin always tied his transcdisciplinary insight back to the political struggle that besieges us. For example, without hesitation, Amin wrote of “democratisation” as the “universalist alternative” to capitalist democracy and its “human rightsish” discourse in a piece titled “The Democratic Fraud and its Alternative” (Monthly Review,October 2011). While including questions of economic management, Amin emphasises that democratisation is an unending and unbounded process involving all aspects of social life. He urges against sanctified formula of “the revolution”, and rather for revolutionary advances and the development of people’s powers through mobilisation, organisation, strategic vision, tactical sense, choice of actions and politicisation of struggles.

Unlike most of his peers, Amin published in a variety of spaces, strategically, depending on the political moment. In March 2016 I was pleasantly surprised to find a renewed rendering of Amin’s delinking, echoing principles of la Via Campesina, in a note he posted on his Facebook. Searching for a solution to deepening inequality and impoverishment in not only African countries, but all countries of Asia and Latin America with national rural populations exceeding 30 percent — Amin elaborates a vision of state-led industrialisation driven by the revival and ecologically sound modernisation of peasant agriculture, to the end of national food sovereignty.

As with Mama Miriam, always a new “discovery” with Papa Samir.

*

We have an aunty in Johannesburg in the public health system who has gone for nine months without a definitive diagnosis of what we believe is a returning cancer. We have another aunty in Johannesburg who has completed treatment for cancer in the private health system in exactly the same time period. As long as such inequality continues for our aunties, uncles, parents and children, Samir Amin’s work will be a tool for change in the Cradle of Humankind and the world that has come from it.

* Salimah Valiani is a poet, activist and researcher. She has published four collections of poetry. She is also the author of Rethinking Unequal Exchange: the global integration of nursing labour markets(University of Toronto Press: 2012) and editor of The Future of Mining in South Africa: Sunset or Sunrise? (2018).

[i]Available for free at https://epdf.tips/neo-colonialism-in-west-africa.htmlaccessed on 1 February 2019

- Log in to post comments

- 3299 reads